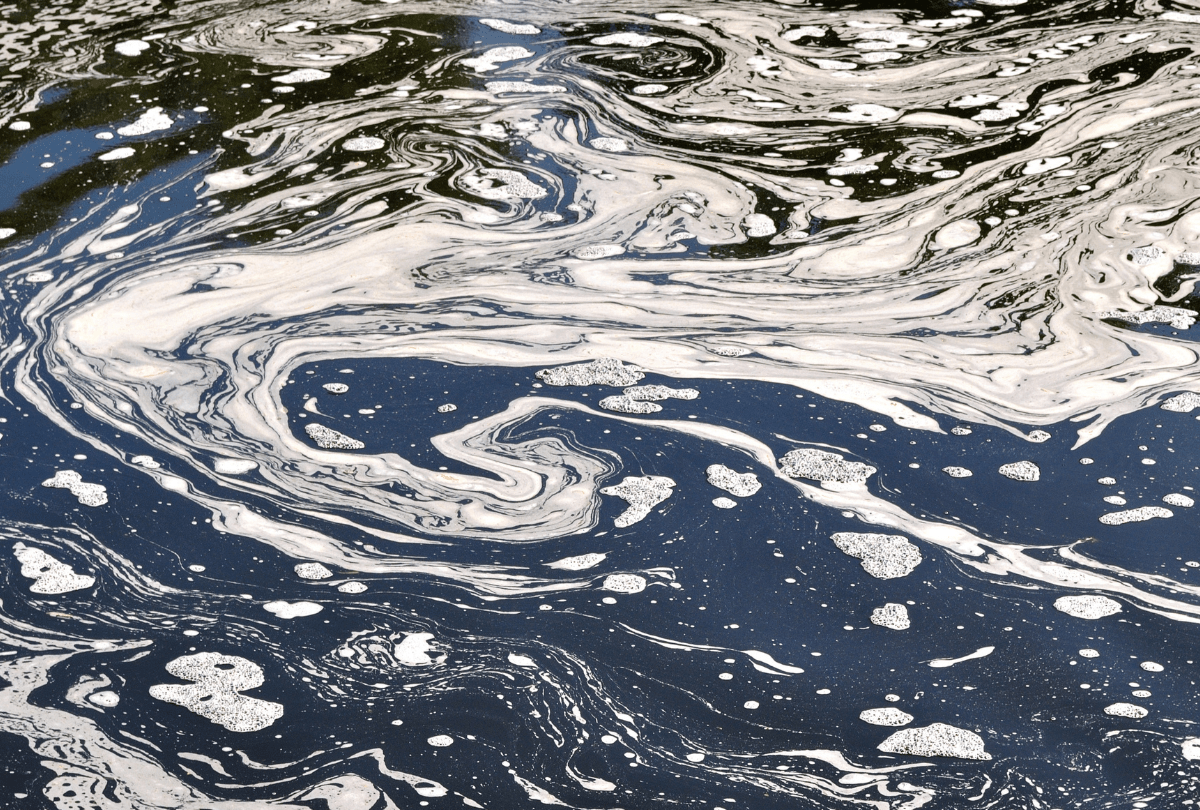

On 3 November, thousands of people joined the March for Clean Water to demand more action to clean up our waterways. They have a right to be angry: only 14 per cent of UK rivers are in good ecological health, threatening nature and rendering them unswimmable. But, while sewage pollution has had plenty of attention, water pollution from agriculture is being overlooked, by both the public and government, despite the problem being just as bad and just as big.

The government has fast approaching targets to meet on water quality. These include legally binging targets to reduce diffuse pollution by 40 per cent by 2038 in the Environment Act, and a target under the Water Framework Directive for 77 per cent of rivers to be in good health by 2027, which it is almost certain to miss.

Failure on one priority must not scupper another

Progress is also needed on housebuilding, another of the government’s major priorities, which is being held up in catchments that are already highly polluted. The additional nutrients new buildings would add in runoff to rivers have to be more than offset by improvements to agricultural practices to avoid failure on one government priority scuppering another.

The government has taken steps to crack down on polluting water companies, such as introducing the Water Bill and the launch of the independent commission on the water regulatory system. While welcome, these are unlikely to meet the targets alone. Tackling sewage pollution will take time due to the scale of the infrastructure upgrades needed. The government has to find another route to progress over the course of this parliament, and that should be to cut water pollution from agriculture.

This type of pollution can either be from a discrete point, such as a leaking slurry store, or diffuse, caused by an action spread across a large area. Sources of diffuse pollution tend to be much more difficult to identify and deal with. It arises when nutrients, primarily nitrogen and phosphorous applied in the form of manure or inorganic fertiliser, are washed off the surface of fields into water courses. It usually happens when they are applied in excess or during wet weather. If not taken up by plants, excess nutrients can also leach through the soil into groundwater, eventually ending up in rivers.

Agribusiness’s profit drive leads to bad practice

Livestock farming is a primary cause of agricultural water pollution and has been clearly linked to the fast and devastating collapse of river ecosystems, such as in the River Wye. Analysis from Sustain found that the ten biggest agribusinesses in the UK are responsible for more excrement than our ten largest cities, but none have publicly available strategies to prevent water pollution.

It is important to look at the influence of businesses operating beyond the farm gate, as their drive for profit pushes down standards along supply chains. Regulation should ensure they take responsibility for, and bear the cost, of pollution arising where they are sourcing from. Smaller farmers at the end of the supply chain have such tight margins that they have little agency to change the system or pay for restoration.

In his speech at the 2024 Labour party conference, the Environment Minister Steve Reed indicated his readiness to work with farmers to “stop animal waste, fertiliser and pesticide pollution ending up in our waterways”. These words now need to be put into action.

Regulation can do the heavy lifting

Our recent briefing outlines ten recommendations, from quick wins to longer term action, to tackle pollution from agriculture. Given the government’s fiscal constraints, regulation will have to do the heavy lifting to make progress. And more of the farming budget should be directed to support farmers to change.

Over the next six months, the government should reform the regulatory framework for the water industry with the aim of raising substantially more private investment in nature-based solutions and reducing the cost to the public purse. Loopholes in the Farming Rules for Water, which have enabled unchecked pollution of the River Wye by the chicken industry, must also be closed.

Over the next year, new guidance should be given so the Environment Agency can effectively enforce the rules. This will prevent polluting farms undercutting those who follow best practice. And those agrifood businesses which dominate supply chains and force farms to work at very low margins should be held accountable and persuaded to offer farmers a fairer deal.

Using the existing farming budget to restore more peat and plant more trees will also improve water quality. To enable this, more of the budget should be directed into the Higher Tier and Landscape Recovery Schemes which can support smaller marginal and upland farms in water catchments. Continuing the Slurry Infrastructure Grant, and allowing small farms to access larger grants, will improve slurry management and prevent runoff into water courses.

Sustainable food strategy should play a part

Perhaps the greatest impact could come from a new food strategy, aligning demand better with what can be sustainably supplied, to prevent unassailable demand for food driving water pollution and environmental degradation.

Taken together, our analysis shows that all of these actions are cost neutral and would minimise the regulatory burden on small family farms, shifting it to the big businesses who are driving the problem and more able to pay.

To return our rivers to health, giving people confidence they are safe again, and support nature to thrive, cut water bills and enable more housebuilding, the government has to take the opportunity to act decisively now on agricultural water pollution, and make a clear break from the failures of the past.

Discover more from Inside track

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.