“We are in a unique position to lead the way on carbon capture technologies,” said Claire Coutinho, former secretary of state for energy security and net zero under the last government. She was speaking at the launch of a vision for the carbon capture and storage (CCS) industry, and went on to say that it “will cut emissions from our atmosphere, while unlocking investment, creating tens of thousands of jobs and growing the UK economy.”

The new government has also supported the technology, with Sir Kier Starmer saying in a speech to the Scottish Labour Conference in February that it would give North Sea oil and gas workers and their communities a future, “not just for the short term – but for decades”.

For a less optimistic take, on the other hand, newspaper columnist George Monbiot says “CCS has been the magic fix for climate breakdown promised by successive UK governments for 20 years – and never delivered… The sole purpose of CCS is to justify the granting of more oil and gas licences, on the grounds that one day someone might be able to capture and bury the CO2 they produce.”

So who’s right? The answer, as ever, is it’s not that straightforward.

CCS has a chequered historyGeorge Monbiot is right to point to past failures. The UK is currently on its third attempt at getting CCS off the ground, with two previous funding competitions cancelled in 2011 and 2016.

Most existing CCS schemes around the world were designed to maximise oil recovery from old wells and have failed to capture as much carbon as hoped. Norway’s schemes are often held up as a case study of success but, even there, it hasn’t all been plain sailing.

Oil and gas companies are desperate to use CCS as the escape hatch that allows them to continue extracting fossil fuels. So far, they have successfully convinced politicians of the beneficial link between CCS and oil and gas industry, with Rishi Sunak moving the Scottish Acorn CCS project into position for funding as he announced more oil drilling last summer. If CCS enables the release of more carbon into the atmosphere, by using the carbon captured to pump more oil out of old wells (called enhanced oil recovery) or by directly linking its development to new oil and gas extraction licensing, it’s not going to be the answer to climate change.

Nonetheless, almost all pathways to net zero will require some form of carbon storage, and eventually net negative emissions. Crudely, the more people’s behaviour changes, eg fewer people eating meat and flying, the less carbon storage will be needed, but this is politically challenging. And there are some economic sectors, such as cement, where even radical behaviour change won’t remove the need for CCS.

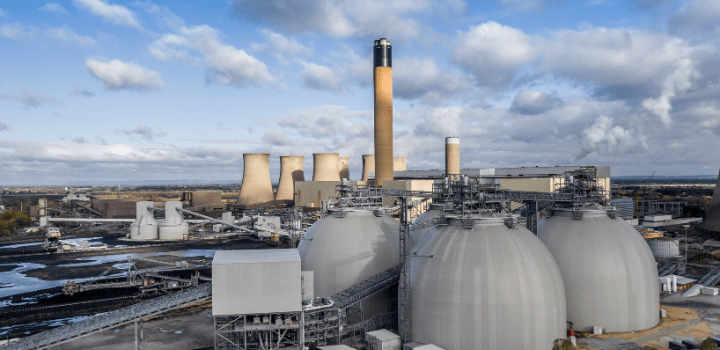

Some CCS uses are easier to justify than othersWith current approaches to achieving net zero so reliant on CCS, we need to know very quickly if it can work at scale in the UK, so we can rapidly pivot to alternatives if necessary. Indeed, CCS has already been out innovated in many sectors. For instance, the original UK CCS competitions were aimed at coal fired power stations, now phased out. Next in line were gas power plants, but the gap filled by existing unabated plants in balancing out renewables can also be filled by hydrogen or energy storage. For industrial emissions, some sectors like steel have already found better alternatives. Alternative technologies are also appearing in cement making, but not yet at scale. And the UK’s fertiliser industry, which was keen to make use of CCS, vanished while the UK government struggled to get policy off the ground.

We might need CCS for a while to make ‘blue’ hydrogen from natural gas, but neither this nor waste incineration, nor the kind of bioenergy with CCS being proposed at scale by Drax, look like long term solutions in their respective niches. Policy makers need to recognise the short term nature of these potential interim solutions and avoid locking in and over-building them.

As hierarchies of use drawn up by Bellona, E3G and others show, it’s only greenhouse gas removal direct from the atmosphere and a few other applications that look like solid long term bets for using CCS. It isn’t a cheap technology. It will always mean extra cost at the end of a process.

Subsidies are distorting decisions about cutting emissionsThe tricky finances around CCS and pressure from its developers have resulted in a flurry of ‘business models’ – a polite way of saying ‘subsidy systems’ – for every possible corner of a future CCS universe. Several projects are negotiating subsidies with the government, with two projects due for final investment decisions this autumn. The previous government promised £20 billion to get CCS up and running, but it’s not clear whether the new government is committed to this level of spending. It has promised £1 billion from the National Wealth Fund and support through Great British Energy.

If the new government continues with piecemeal subsidy, it risks distorting industrial decarbonisation decisions. For instance, if CCS and blue hydrogen are subsidised but electrification isn’t, industries like chemicals looking for solutions might opt for a route that attracts 15 years of taxpayer support, rather than the best long term option to cut their emissions.

There’s also the question of who ultimately pays: taxpayers, energy bill payers or fossil fuel producers. Currently, the taxpayer is supporting the industry through CCS business models. The previous government’s vision for CCS promised to move to a market-based approach which, if designed right, should ensure polluters pay. The UK emissions trading scheme could be used to fund CCS or a ‘carbon take back obligation’ could be developed which makes fossil fuel producers fund and develop carbon storage.

There are still good reasons to rapidly trial CCS in a UK context, not least to be clear if we need a plan B. But that shouldn’t preclude having a more open debate in the meantime about where it might be useful, where it almost certainly won’t be and who should pay for it.

Discover more from Inside track

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.